Is the Creative Commons License Valuable for Academic Work?

The Varieties of Academic Production or What would William James Have Done Given the Opportunity?

Many different kinds of work go on in Universities. Scholarly work may or may not result in publication, and the type and purpose of the work differs by discipline. Some researchers may be interested in sharing pedagogical work that takes the form of syllabi, assignments, or teaching approaches. Poster or panel presentations contain the seeds that lead to work that is intended for publication and a scholar may choose to share such work to gather feedback or critique without compromising future publication opportunities. Some genres of work are more likely to be self-published than released through commercial or other third-party publishers. For instance, in the academic world, musical compositions, videos, musical recordings, and works of design might fall into this category. Each of these creation types might be more comfortably released into the public sphere with a CC license. Whether a CC license is appropriate for some or any of this work would require detailed and painstaking analysis—school by school, department by department, discipline by discipline, with all of the nuances of purpose, expectation, and aspiration kept in mind. At an early stage, the creator has possession of all the exclusive rights granted by copyright, and so the choice of how and whether to make work publicly accessible will be completely in their hands

CC licenses allow the author/creator to maintain attribution and to determine the extent to which the material is used. Applying CC licenses to materials such as those mentioned above, allow the creator to establish a clear path for use, adaptation, and distribution. The advantages of making use of the CC licenses are multiple. A prominent advantage is that creators can clearly state their desires and expectations for the (re)use of their creations. Users coming to the material have clear instructions on what they may or may not do with the material. The CC license rests on the foundation of copyright, and unless the creator dedicates their work to the Public Domain, copyright continues undisturbed. The creator can define the way in which they choose to share elements of their “exclusive rights” under copyright, without ceding any of their own rights to make use of the material as they see fit. CreativeCommons.org has monitored the legal decisions that have involved CC licenses. So far, the decisions have supported the validity of the licenses. See https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/Case_Law for a review of case law so far.

Lawyers and Deeds

There are multiple layers to the licenses. As time has passed since the first licenses were issued in 2002, the CC organization has adapted them to meet expressed needs and to incorporate the results of their continued analysis. The layers include the “lawyer readable” text, which is the legally binding version of the licenses, the “human readable” text or “commons deeds,” which is what most of us as creators and users will use for guidance and decision making, and finally the “machine readable” or “CC Rights Expression Language” that summarizes the key elements for use granted and the obligations asserted in a technology, search engine friendly format.* Exploration into these three layers, belies the simplicity of the familiar “human readable” interface, and some of the elements, including noncommercial, or ShareAlike, may be less intuitive than we expect, but, for the most part, a scholar, coming to these licenses should be able to discern the license that will work best for them, and meet all of their needs and concerns.

Here is what you need to know to get started–and be sure to visit creativecommons.org to fully explore your options and understand to your comfort level, the motivation and purpose behind this suite of licenses.

Four Elements Can Be Combined to make Six

There are four elements (each with their own icon), that come together in a variety of ways to create six licenses (also with accompanying imagery). Since 2002, the licenses have gone through five iterations (1.0, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, and 4.0). CC urges creators to make use of the most recent versions—which are designated as 4.0

The four elements are

- BY — as in created “by whom”?–All licenses require the re-user to give credit or attribution:

- SA, or ShareAlike. This means that if you use or incorporate CC-SA licensed material into your new creation, you must share your new work under a compatible license. The spirit of the CC-SA license must stay with the material even if it is adapted or transformed.

- NC, or Noncommercial, means that the work can only be used for noncommercial purposes. Noncommercial does not apply to the user, the user could be the Disney Corporation, as long as their purpose is noncommercial – for instance, making use of a figure you’ve created to brighten up packets of food that they have made available at a disaster location—and that preferably (to my mind) wouldn’t include their corporate logo. A hypothetical case, of course.

- ND, or No derivative, means the work cannot be adapted AND shared. If the user does adapt the work, they cannot share it publicly.

These four elements and their icons combine into six licenses (click on the icons inserted below to get all the details about the license and to get started using them).

The Mighty Six (If you look up “famous sixes” in Google, you get a lot of links to great moments in Cricket)

- Attribution license — CC BY allows users to use the material in any way as long as they provide attribution to the creator. This is the most open of the six licenses. For an even more open approach, see “Public Domain” below.

![]()

- Attribution-ShareAlike license — CC BY SA. Based on the description of ShareAlike above, you can guess that this means you can do what you like with the CC BY SA licensed creation as long as you provide attribution and share the resulting work under a similar license. It is also recommended that you provide a link or other information that directs potential users of your creation to the original upon which yours is based.

![]()

- Attribution-NonCommercial license–CC BY NC. If you apply this license to your work, you are letting future users know that you expect them to give proper credit and that your intended use cannot be commercial. It is written into the licenses that if a user violates a term of license, such as the requirement for noncommercial use, their right to use the licensed creation can be revoked if the violation isn’t corrected within 30 days.

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license—CC BY NC SA. Are you starting to understand how these licenses work? Yep—If you are going public with your own creation, either containing or adapted from the original licensed work, you must share it under a similar license, and that includes no commercial use

![]()

- Attribution-NoDerivatives license–CC BY ND. The restrictions increase as we work our way through the licenses. This license drops the “noncommercial” but incorporates “no derivatives.” This means that the licensed work must be used as you found it. You can’t add a mustache and then make notecards that you are going to sell online or at a farmer’s market. You can’t turn the novel into a play or film script and then distribute it to the public, commercially or noncommercially. It is possible that the creator would allow you to do this, but you would have to seek permission.

![]()

- Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license–CC BY NC ND. Finally, the most restrictive of the six licenses restricts both the ability to adapt a work that you plan to share and restricts commercial use of the item.

![]()

You can “insert” the image or embed the html code into your work, linking to its accompanying documentation.

Wait, There’s More

In a previous post, we talked about the four factors of Fair Use. Regardless of any restrictions incorporated into the six CC licenses, Fair Use outranks all of them. If you are a re-user, and your use falls within the framework of Fair Use, should your use be challenged, you should be able to defend yourself on the grounds of Fair Use. Should this really become an issue and you were to end up in court, you will likely want to consult with a lawyer. But, the rumor is that the CC using community is a reasonable group of people filled with good will and the will to share. It is possible that you would be able to discuss your use with the creator and come to an amicable agreement that suits both your needs and the creator’s expectations. Remember, no matter what, it is always best to give credit where credit is due. You will want the same!

Stairway to Open Access

We promised to say something about the Public Domain, but you were younger then and had a greater ability to concentrate. But, just in case you’re hanging in there–Copyright lasts a long time, but it does run out, and at different times in its history, it has run out sooner rather than later. That means there is a great deal of creative work that is in the public domain. This is just a legal situation. Many of the great classic works of literature from all literary cultures are in the public domain. In the United States, most works published before 1923 are in the Public Domain, Government Documents are immediately in the public domain, and a creator can dedicate their own work to the Public Domain. CC has what they call a Public Domain Dedication, CC0.

This puts your work out there with no restrictions whatsoever. Barnes and Nobles could add your novel to their nice and inexpensive edition series, someone could use an image of your painting as the cover of their next scholarly work without asking permission or paying royalties or being challenged in the future. Once something is in the public domain, copyright does not apply. Since Creative Commons licenses are based on copyright, they do not apply either.

For your Consideration

Why would you want to apply a CC license rather than dedicate your work to the Public Domain? Certainly, if you are planning on publishing your work, with either a not-for-profit or for-profit publisher, you’ll be likely to find that your publisher will want to be able to acquire some of your rights at least for a time before making it freely available (read your contract!). Beyond that, applying a CC license allows you to maintain control over your own work and how it is used: you’ll have some assurance that the integrity of your work will not be compromised, that your name remains associated with your own work, and that you have a better chance of challenging potential misuse or misinterpretation of your work. The CC licenses also allow you to disassociate yourself from adaptations that might be put to uses that are anathema to you.

A last word on Open Access and Creative Commons Licenses

What if you want to incorporate something into your own creation that is in the Public Domain? Go right ahead! However, when you apply that CC license to your newly created work that is built, in whole or in part, on elements from a public domain work, you can only license the unique elements of your work – you cannot license the public domain aspects of your new work. Once in the public domain, always in the public domain. Disney Corporation can’t, for instance, stop you from using the story of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. The original fairytale is in the public domain. They can, however, prevent you from using the music from its animation, or for using the names its writers and artists created for those seven dwarves, or using images derived from their animation . . .

Say the word and you’ll be free..

*Language adapted from segment 3.1 of the Creative Commons Certificate Course

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

[This image is taken from the actual text of the Extension Act. As a publication of the United States Government it is in the public domain. ]

[This image is taken from the actual text of the Extension Act. As a publication of the United States Government it is in the public domain. ] [Taken from the

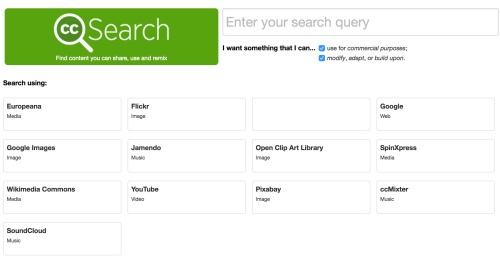

[Taken from the  [https://search.

[https://search.